By Matthew Grimes, Reader in Organisational Theory & Information Systems and Academic Co-Director of the Entrepreneurship Centre at Cambridge Judge Business School.

As an early-stage entrepreneur, I attended a talk given by a successful serial entrepreneur, where the title was “How 17 Pivots Turned into a Successful Acquisition”. The talk was largely organised as a series of entrepreneurial war stories that illustrated the various trials and tribulations that the entrepreneur had encountered as he developed his first venture. I believe the key intended takeaway was that because entrepreneurship is full of uncertainty, the only way to be successful is to throw your ideas out there, hope they stick, and when they don’t, you need to learn from the failure and be willing to revise those ideas until you get traction with customers and investors.

Looking back, I would categorise this talk and these takeaways as part of the “fail fast” or “fail forward” vintage. Perhaps you have heard these mantras referenced in the context of your entrepreneurial journeys? If not, all you need to do is google them, and you will find a series of presumably inspirational banners. The idea is that rather than viewing success and failure as opposing outcomes, we need to instead view success as a journey, and one that actively embraces failure and learning as a part of that journey. In order to encourage founders to adapt their business models after experiencing failure, many entrepreneurship gurus have embraced the concept of pivoting, initially popularized by Eric Ries and the lean startup methodology. Indeed the term has now become so popular that Ries has highlighted this cartoon from the New Yorker as an indication that term is starting to seep into our everyday lives.

How should you think about all of this? Should you join in on the celebration of pivoting as the key to entrepreneurial success? As an entrepreneurship educator and researcher, I am generally supportive of the pivoting metaphor as well as the underlying focus on experimental learning. However, in our rush to embrace concepts such as pivoting, failing fast, and others, I am also concerned that we may actually be losing sight of why the pivoting metaphor is in fact, a useful one. The concept of pivoting, of course, is drawn from the sport of basketball, wherein the player has one foot planted while allowing degrees of freedom by rotating the other foot. However, think back to the last time you heard somebody invoke the term pivoting. How was the term being used? My guess is that they were using the term interchangeably with the notion of adaptation, without any regard for what was remaining the same. When we speak of pivoting in new ventures, we are now hyper-focused on the benefits of changing direction (even 17 times!), but we have lost sight of whether or not our other foot has remained steadfast.

As entrepreneurs, what do we lose when we over-focus on change and adaptation? Well, for one, we lose time and resources. We have to dismantle any existing routines and associated efficiencies we might have developed around the current business model, and then our organizations have to spend time and new resources learning to execute on a new one. As you well know, the length of your entrepreneurial runway is finite, and with every business model change, you are speeding toward the edge of that runway. Second, by changing our business models we risk losing our own commitment to the venture and even losing the loyalty of our stakeholders. In a recent study, I illustrate how most entrepreneurs feel a sense of psychological ownership over their early ideas (Grimes, 2018), and other recent work has built on this, revealing that the early external supporters of your business are also likely to develop a sense of identification with your business models (Hampel and Tracey, 2019). Constant changes to your business are thus likely to threaten not only the flow of resources and support into your organization but also your own willingness to persist.

With all of this mind, let me offer you an alternative model of entrepreneurial success to that of “fail fast and break things.” Let’s call it structured flexibility. It’s an approach that recognizes that although new ventures clearly need to be adaptive, they also need to ensure that as they change, they are upholding their core. Keeping one foot rooted in the central values and ideas that made you decide to become an entrepreneur, while allowing yourself the flexibility to experiment with new directions. This may seem paradoxical, but as F. Scott Fitzgerald opined in 1936, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” I believe this is particularly true in the context of entrepreneurship, wherein founders are faced with a number of seeming and ongoing trade-offs.

|

|

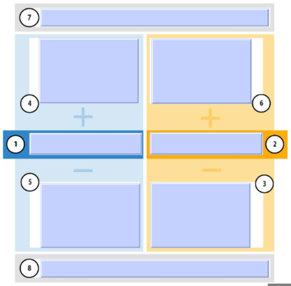

But developing this first-rate intelligence is a skillset, and you must train yourself to think about how you will balance the ostensibly competing objectives of determining and retaining what is core to the business while adapting the parts of your business model that need to evolve. Figure 1 offers a simple tool that I would encourage you to use as you try to manage this trade-off. |

It is called the Polarity Map, and I would suggest that the next time you need to change your business model, you fill out this tool in the following way:

- Write down the business model change you feel is necessary in order to improve your venture’s viability.

- Write down the core part of the existing business model you want to protect as you pivot.

- Write down the unintended consequences of an over-focus on the existing business model the exclusion of the proposed change.

- Write down the benefits associated with the newly proposed business model adjustments.

- Write down the unintended consequences of an over focus on the new business model to the exclusion of the parts of the prior model you wish to protect.

- Write down the benefits of a focus on the old approach.

- Reflect on the broad value proposition of your company, which encompasses the upper half of this model (cells 4 & 6).

- Reflect on the broad risks, which encompass the bottom half of the model (cells 3 & 5).

And next time an entrepreneur tells you that they are pivoting, instead of asking them what they are changing, start by asking them what they are retaining.

This article was written by an independent third party and the views contained within are not necessarily the views of Barclays. This article is designed to help you with your independent research and business decisions. This page contains link(s) to third party websites and resources that we (Barclays) are not providing or recommending to you. The information contained in this article is correct at the time of publishing. We recommend that you carry out your own independent research before you make any decisions that will impact your business.

Barclays (including its employees, Directors and agents) accepts no responsibility and shall have no liability in contract, tort or otherwise to any person in connection with this content or the use of or reliance on any information or data set out in this content unless it expressly agrees otherwise in writing. It does not constitute an offer to sell or buy any security, investment, financial product or service and does not constitute investment, professional, legal or tax advice, or a recommendation with respect to any securities or financial instruments.

The information, statements and opinions contained on this page are of a general nature only and do not take into account your individual circumstances including any laws, policies, procedures or practices you, or your employer or businesses may have or be subject to. Although the statements of fact on this page have been obtained from and are based upon sources that Barclays believes to be reliable, Barclays does not guarantee their accuracy or completeness.